Lady Prudence Alessandra Maccon Akeldama—better known as “Rue” to her friends and quite deservingly so—is causing havoc all over London society. It doesn’t help matters that she’s related to the three most powerful supernaturals in the British Empire: daughter of the werewolf dewan Lord Conall Maccon and preternatural Lady Alexia Maccon, and adopted daughter of vampire potentate Lord Akeldama. On top of that, Rue possesses her own unique abilities; she is a metanatural (or “skin-stealer”), who can temporarily take the powers of any supernatural she touches.

Lady Alexia thinks its high time for Rue to put a stopper on her wild behavior, and Lord Akeldama wants to send her on a mission to acquire a new variety of tea leaf. Thus begins plans to send Rue off to India in a dirigible of her own naming—The Spotted Custard—along with a slapdash crew of the best and brightest (though some members are also the most irksome to Rue). What awaits in India, however, is a revelation that could possibly change the geopolitical balance of the entire Empire.

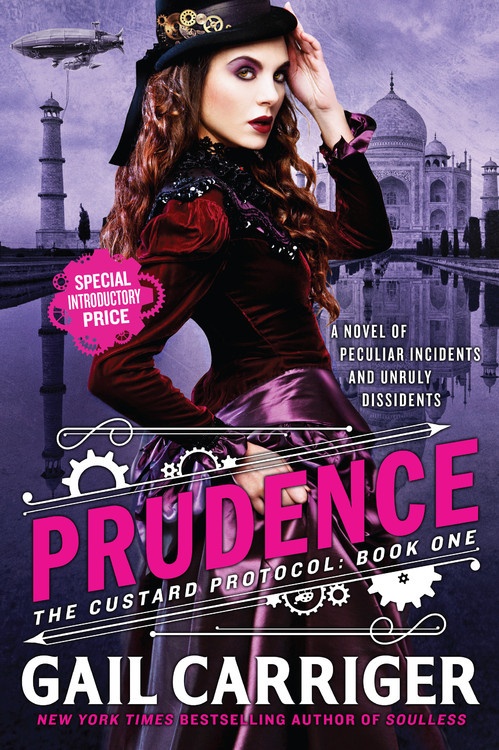

Prudence is the first in the Custard Protocol series, Gail Carriger’s highly anticipated follow-up to her Parasol Protectorate series. At the tail-end of the first series, we got a glimpse of the rambunctious Rue, and now she’s all grown up and ambitious to start her own globe-trotting escapades.

In some ways, Prudence does not disappoint: Carriger’s witty prose is at full force and her characters are a frothy delight. We see the new generation take a life of their own, while also building upon connections from the cast readers loved from the Parasol Protectorate. Akeldama’s schemes and fashion sense steal every scene. We get a new perspective on Alexia from a daughter who certainly isn’t fond her. Quesnel, who was a child in the first series is now a very mature—and very dashing—engineer. Their flirtatious dance of “Is he/she serious or not?” is compelling to read. Also joining the crew are the Turnstell twins: Primrose—not as over-the-top as her hat-toting mother Ivy, but quite close—and her awkward and bookish brother Percy. Later faces show up in India made me appreciate the read all the more. New characters are also introduced to round out the cast, including the mysterious Miss Sekhmet and a ragtag group of hyperactive deckhands and the contemptuous engineer Aggie Phinkerlington.

Rue herself has a long way to go in terms of emotional maturity. Like how she can steal supernatural powers from any preternatural she touches, another quirk she has is lifting mannerisms from her friends and family. In a given situation, she chooses who to act like as the best solution to handling herself. As insightful as it is to have Prudence rely on “persona” shifting as much as actual shifting, the result is her constantly playacting instead of being genuine to most people she interacts with. Her friends warn her not to depend on having a convenient vampire or werewolf around to snatch their powers in a tight spot; similarly, I also hope that Prudence stops relying on this habit in future books.

Another quality of Rue that bothered me—and one of the thornier issues I had with the book as a whole—is her perspective on India and other people of color. Carriger doesn’t sidestep the reality of British attitudes toward the Raj, which in Rue’s eyes is mostly delightfully picturesque (though she is dismissive on how they take their chai). On the other hand, some of Rue’s descriptions have a racist undertone—quite literally, since she’s talking about non-British shapeshifters and vampires. In Prudence, people of color are either objectified or demonized.

In one passage, she notes how the Indian vampire differs from the British variety: “Rue expected him to look like any other vampire, only Indian in appearance. Mostly he did. Mostly. But it was in the vein of how a broad bean looks like runner bean—different, but both still beans.” What follows is a demonic description of the vampire that contrasts with the elegance of the British variety and ends with the observation: “This creature showed outwardly that he was a bloodsucker, with no pretense at anything civilized. The lack or artifice was off-putting, not to say embarrassing, and explained the crew’s reaction.”

In opposition another PoC main character is constantly described by her immense beauty—which in itself is fine, but gets discomforting when her physical beauty and her animalistic aspects are the two qualities Rue dwells upon the most. Later on, she describes another Indian shapeshifter (not saying what variety because it’s another major spoiler) as “comely with dark almond eyes, ridiculously thick eyelashes, and velvety tea-colored skin.”

Granted, many of Carriger’s characters describe each other in terms of food; Lord Akeldama is notorious for his culinary-inspired terms of affection. But Rue using the same language has a different impact when describing people of color, who have a long history of being objectified by being seen as consumable items—on top of the context that she is on a mission to steal tea from the Indians.

Despite her undeniable imperialist leanings, Rue resolves the book with an agreement which puts some Indian characters at a more favorable advantage against the British Empire. But Carriger is also honest about her British characters’ attitudes as being the “civilizing force” in India, and many of them state “white man’s burden” arguments during one climactic scene that cut into the fun that most of the book contains.

Thus, what starts off as characters’ fun snarky attitudes in the Parasol Protectorate series become a sign of paternalistic arrogance that is symbolic of British imperialism itself. You laugh at various characters for their wit, but feel a twinge of annoyance at their motivations as well (or at least I did) that the humor cannot overcome. In this, Carriger had perhaps achieved a successful slow-burn toward a critique of empire, one that took the completion of the Parasol Protectorate to before it became completely exposed. Rue and her British compatriots—for all of their charm and witty banter—uphold a national attitude that damaged as much as they believed it uplifted.

Prudence is available March 17th from Orbit.

Ay-leen the Peacemaker (or in other speculative lights, Diana M. Pho) works at Tor Books, runs the multicultural steampunk blog Beyond Victoriana, pens academic things, and tweets. Oh she has a tumblr too.